My mother—stiff, straight-backed, her mauveine headdress held high and mighty above my bedroom door—glares dark suns into my eyes. That is how I know they’ve discovered what I’ve done, and a surge of weakness runs through me, pooling at my feet. I wait for Ma to speak in the stuffy warmth of a night lit by frail candlesticks. When she does, her voice is low, frigid, angry.

“Where is Eneji?” she demands slowly, each word enunciated with cold, serpentine delicacy.

I’d prepared for this moment a hundred times over in my mind. Two responses were open to me. One was to flat-out lie: I didn’t know where Eneji was. My bumbling daughter of nine with hair the color of ripe hazelnut was born with a nomad’s wanderlust. Check the corn farms at Apata. Or go to Ofuroba where there are so many breadfruit trees and cashews glimmering yellow and supple on their buds. She might be there somewhere, touching life where it is still sweet. Don’t ask me, I planned to say, I don’t know.

The other response demanded too much liver; even more than it’d take to stare an egbé masquerade—in all its belligerent ugliness—in the eye. I imagined myself standing tall, fiery-lipped like Ma, and with the gall of a chest-beating mountain gorilla I would declare to her face: “I will NOT give up my daughter for you to razor into a half-being,” and then spit on the earth so she knows I am drawing èkètè, the soil goddess, into my oath.

But where would I find the liver? So I keep my lips mum and stare at the cold elegance of Ma’s headdress, the coral beads patterned into triangles on the side, the oyster shells crowning the peak. It strikes me then how doubly atrocious it is that it is I, the daughter of the most important woman in Ida, who plans to stump this season’s blood rite.

“Bring Eneji to us before sundown, or else.”

My mother is too decisive a woman to wait around for my indecisive mouth to frame a proper lie. As she stalks away, the air does not stir and the beads on her headdress rattle in time with her footfalls.

I ask myself what or else really means. For me, a dank ostracism. A branding for shame. Ah! What sort of a mother would not let her daughter be circumcised? How can any woman with a clear head wish that her daughter forever never crosses the threshold into womanhood? Then they’d spit at me and eye me over as I returned from Maami stream on bright-eyed mornings.

For Eneji, I don’t know. The women told us when we were young and played with clay in front of our parents’ huts, that our bodies carried a great sin. The little thrust of flesh on our flowers was iwa – filth. To be a true woman was to lose the flesh, to be free of its filth and gain purity. We did not know this process was mired in too much blood. And that our bodies would never recover.

***

The day Ma, straight-backed as ever, came to fetch me, there were many lizards frolicking in the yard and I was chasing them with the catapult my father fashioned for me out of walnut wood. Night approached calmly. The sun passed from fiery orange to burnished bronze, and soft-eyed stars began to poke lights through the sky. She held my hand and I followed, bored.

“We’re going to see your Aunt Patumo,” she said.

“Oh,” I replied.

“Cheer up,” my mother said. Her voice held no cheer. “Sa’ide is back.”

Oh Sa’ide! I thought. She was Aunt Patumo’s youngest girl, my age, with deep-set eyes as black as midnight. I smiled to myself. There’d be so much catching up to do between us. How long had she been in the township again? 6 months was my best guess. Aunt Patumo’s hut was not too far from ours, and as soon as I sighted it, I broke from Ma’s grip, running to find Sa’ide. I heard Ma yelling at me to come back, but I didn’t listen. I sped into the house and into the bedroom.

There were too many women inside, and someone was crying so loud I felt the sound on my skin. I called, “Sa’ide,” my voice fragile. One of the women turned. Through a gap, I saw Sa’ide on a mat set on the wretched mud floor, a messy puddle of blood around her. It was her cries I had felt on my skin.

I screamed. The woman who turned grabbed me by the hands. I broke free and tried to run out of the house, but Ma was in the way, glaring down at me with her stiff-lipped face. She cuffed my hands in hers and lugged me back to the women. They swirled around me. Ma pinned both my hands and stared deeply into my eyes as the razor, swift and merciless, decapitated me. Then a pain so irate, so implacable, so wildly consummate and so eternal surged through me.

That pain never truly left. That night I still carry with me. It clung to my back as I moved to the township at Waterside. And on the day I met Sotolu, the man whose voice sent large ripples through my bloodstream, it fake-coughed, “ahem, ahem, I’m still here.”

So that one day, I had to explain to my young fisherman lover with brown eyes and walnut hair, that my heart felt a passion that my body was too broken to understand. That my body held no ignitable liquids, no threat of flame leaping upon touch.

When I finally left him and Waterside and ferried back to our village on a misty blue morning, I carried his child, Eneji, within me. Eneji, named for the fragrant plumeria with its snow-white and sulphur-yellow petals in our local tongue. They grew near the teacher’s quarters at Old Ring Road and were the most beautiful flowers I knew.

Eneji arrived on the brink of the harmattan, hurling me into months of torture. Why had the gods decided to give me a girl to continue this cycle of eternal pain? Every single time I looked at her, I wrestled with fatal images: of blood assaulting the sulphur of the frangipani petals near the teacher’s quarters; a rusty razor defacing flesh and blood-letting into the void; Sa’ide on the mud-floor gasping for her mother; my tight-lipped mother pinning down my child—my baby—my Eneji.

***

A little voice is calling my name frantically:

“Aunty Sheya! Aunty Sheya!”

I am stung alive by dread. They have my daughter.

I rush to the door of the living room. It’s Mossia, one of Eneji’s playmates. He’s struggling to catch his breath and I can see from the dirt swaddling his feet that he has run a very long way.

“Aunty I saw Eneji. I saw Eneji with grandma. She was crying, Aunty!”

I have long legs and a rapid, burning will. This is how I leave the wind before it knows what has touched it, and I cannot even hear my footsteps beneath the roar of my one raging thought: they have cut my baby!

There’s a weapon in my hand, a machete. How did it get there? The images—the bloodied petals, the blood-letting razor—dizzy through my mind again, and it becomes increasingly clear to me that I do not care about whatever happens afterwards. If my baby never becomes a true woman—whatever that means. If she never becomes a pure woman—whatever that means too. If pure women were people like Ma, and aunties who nip little girls in their buds with rusty blades, then purity be damned.

I am angry now. I am screaming now.

***

When I burst into Aunt Patumo’s living room, I can already hear wild screams going up into the night. In shock, all the women scamper to their feet and eye my dangerous hand.

“Mummy!” Eneji bawls and I see her for the first time since the night before, when I took her to the boatman’s house and paid him a bag of cowries to take her to Waterside and locate her father.

“Eni,” I say. “Don’t worry. I’m here.”

To my mother, I warn, “Let my daughter go,” with the kind of serpentine delicacy I’d learned from her all my life.

“A man knows what to do. And you, a mother, do not?”

I hear someone say, “Find Edime.”

Edime is Aunt Patumo’s third son. A brawny fellow with a talent for trouble. If he gets here before I leave with my daughter, I’m finished.

“You will not cut my daughter,” I cry at Ma and all the women. “Over my dead body!”

“Calm down,” many voices urge.

“I cannot believe such a fool passed through my legs into this world,” Ma spits. “That knuckleheaded boatman was far wiser than you. He brought Eneji to us this evening as soon as he guessed you were trying to have her flee the blood rite. He knew that Eneji was of age and should be allowed to shed the bad skin.” Ma’s exterior is still as icy as ever, but I can see in her eyes an urgency. “I can see you’re determined to bring shame to this family!”

I hear a noise coming from the yard. Have they found Edime? There’s no more time for words. I charge forward into the shadows, waving my machete with crude, reckless force. Ma leaps out of my way. The women scamper out of the room. I find my Eneji on the stained mud floor; the blood of some other girl who has already been cut slithers hot and red, and I can feel her cries on my skin too. I pick up Eneji and dash for the door. The sounds from the yard are close, really close now. I could be overpowered. My baby could be pried from my arms. I plunge through the door and out into the openness of the evening, bracing myself to encounter an army of brawn.

***

The first thing I see is Edime. There is a surprise on his lips, a machete in his hand, and five women behind him, goading him to suppress me. But something is off. He’s not making a move towards me. He eyes me thoroughly, while sounds of wailing are still pouring from inside the hut, and in that moment we share a heart. I watch his hands unstiffen around the hilt of the machete, his eyes begin to thaw. I know immediately that he will not give chase as I flee into the night. And I do; dragging my baby into my speed. However torturous the pace, her body will remain, as it was meant to be. The second thing I notice is that there are soft-eyed stars out tonight too.

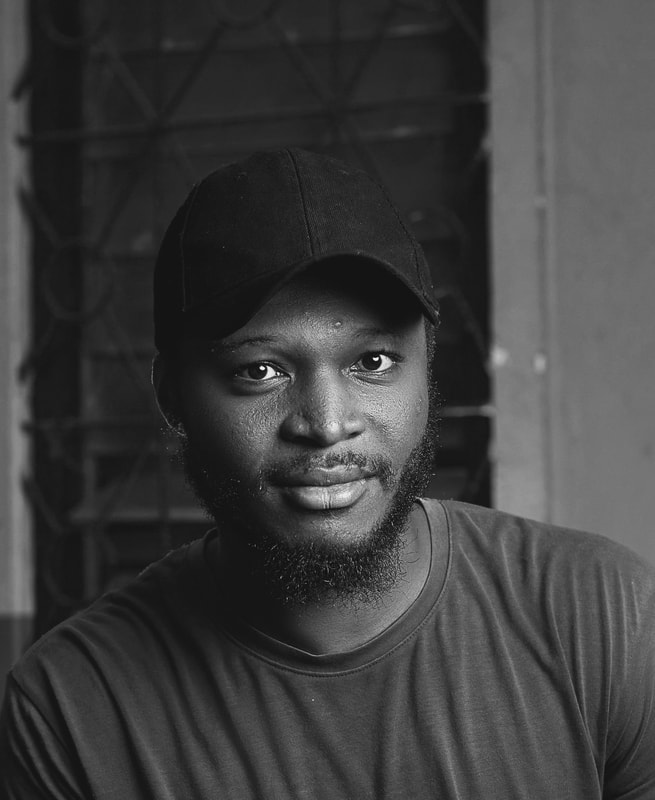

Divine Inyang Titus is an assistant editor at Afapinen and the author of the chapbook A Beautiful Place To Be Born. He is a joint winner of the 2023 Brigitte Poirson Literature Prize for Fiction and a past winner of the STCW Future Folklore Climate Fiction Contest, 2021. His stories and poems have been featured in Brittle Paper, The Ex-Puritan Magazine, Blue Marble Review, The Parliament Literary Journal, The Shallow Tales Review, and elsewhere.