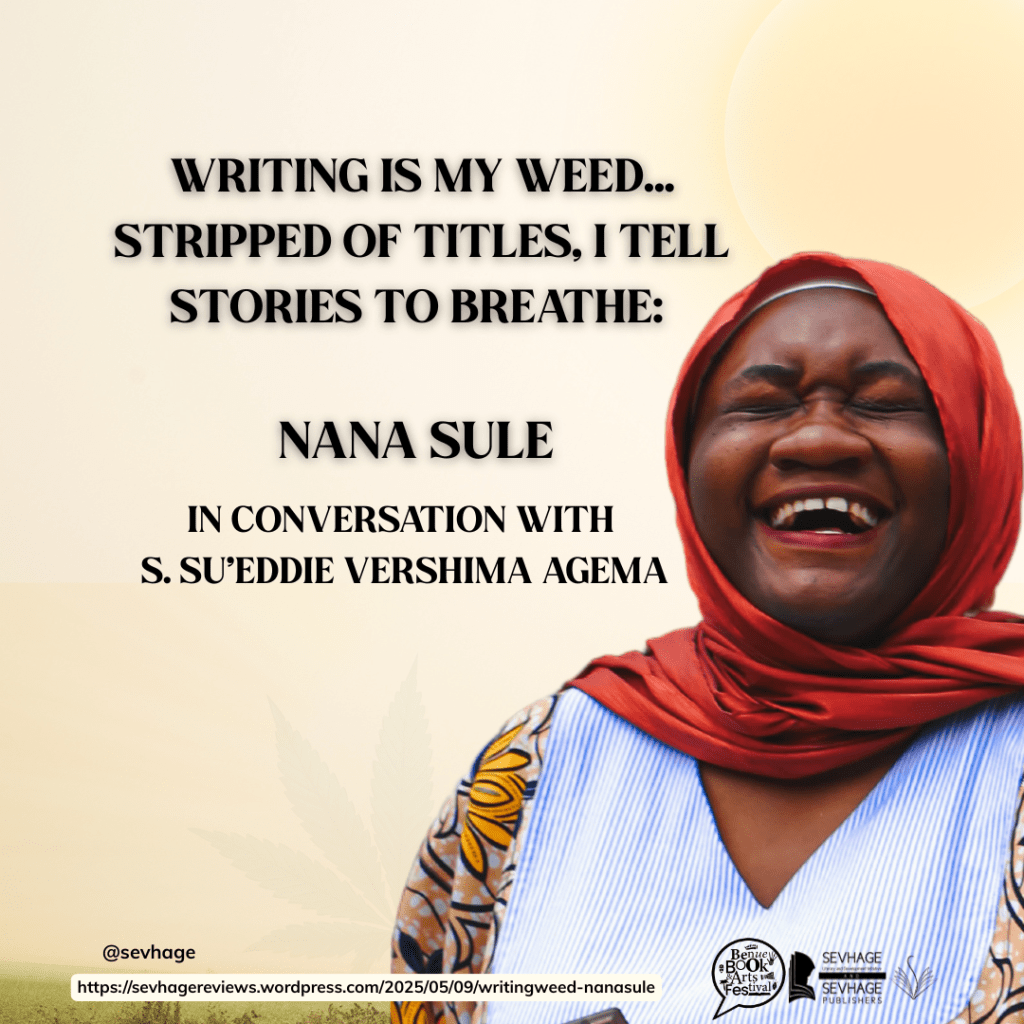

In a literary landscape brimming with talent and urgency, Nana Sule stands out as a voice of tenderness, rage, and profound clarity. Whether writing of broken bodies, smuggled truths, or haunted girlhoods, her work never shies away from the messiness of being. Her debut collection Not So Terrible People and her acclaimed award-winning essays like We Bought an Album in June (Winner, Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction 2024) and Birthing the Mother are proff of this, an arc showing a chorus of women, longing, faith, loss, and unrelenting beauty. In this conversation with award-winning writer and SEVHAGE founder, S. Su’eddie Vershima Agema, Nana speaks about writing as opium, memory as resistance, and the ways she navigates the world as a storyteller, a Muslim woman, and a champion for gender and reproductive rights. It is a conversation about storytelling, but also about survival, silence, and the hunger for light.

Nana, thank you for agreeing to this conversation. It’s a pleasure to speak with you again, especially after having presented your Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction award in Makurdi earlier this year. You were a big part of the Benue Book and Arts Festival in its Makurdi and Abuja rendition. So, let’s start with the big picture before we ease into the stories. Let’s start from the many hats you wear. You’ve been writing for a long time and wearing many hats—author, editor, strategist, bookstore co-owner. But if you strip away the titles, what would you say drives you, really, as a storyteller?

Haha, thank you for chatting with me. I feel so honoured—and not just because SEVHAGE is such an important platform and I respect the work being done here, but also because SEVHAGE has been an integral part of my growth. Su’eddie and Dr. Agatha have supported me in countless ways: emotionally, with my craft, financially, and even health-wise. They are family. So I’m really glad I get to do this with SEVHAGE.

To answer the question, I’m not sure. I want to say something novel and virtuous, like: it’s the need to document our lives or I write to change the world. And maybe these are all part of it, you know? But I think, also, it’s to escape. Writing is my opium, or, what is it the lads are doing these days? Weed? Anyway, you get the gist. Writing—telling stories—is the high that gets me through this world. It restores my hope, returns me to the shore, anchors me when the storms are raging.

You once said you wrote your first story at six and started reading newspapers early. What do you think made you lean into stories at that age? And now, after all these years and experiences, what keeps you leaning in?

Family, for the most part. At the time, I was the last child in my household—the baby of the house. My mum taught me to read and write early, so I could do that from a young age. In fact, I have no recollection of learning to read or write, and since my earliest memories are around five or six, I can safely assume I could read before then.

Now, between me and my immediate elder brother is a seven-year gap. My older siblings were mostly away in boarding school, and my mum was doing a postgraduate degree—I think. I just remember she was always traveling for school. So it was mostly my dad and I at home, and he was a storyteller.

We’d watch Indian movies together, especially the ones with Amitabh Bachchan—we knew all the songs, haha! Amar, Akbar, and Anthony! God, we could sing so many Indian songs. We’d take drives to go get suya, sit by the window to watch the rain, and sometimes at night, lie on a mat outside to watch the skies. You see why I’m a hopeless romantic in real life, abi?

On those nights, he’d tell me stories of talking hares, corrupt birds, crafty tortoises, and more. Other times, we’d watch shows I probably had no business watching at that age—Passions, The Gardener’s Daughter. And on nights he worked late, I’d summarize the episodes for him. He loved to read my summaries.

My dad also loved reading newspapers. I’d sit with him and listen to him lament about Nigeria—lol, ah! We’ve been lamenting about Nigeria for so long fa. It was his idea for me to summarise the news and cast it at the assembly ground. He even spoke to the headmistress of my school and got me the gig, lol.

I think he was trying to make sure I wasn’t lonely, and maybe he saw some potential in me—with words. I’m grateful that he nurtured that. Speaking and writing have always come naturally to me—it’s almost like the air I breathe. And I’m deeply grateful for the gift.

Now, what keeps me leaning in is a sense of responsibility. There’s something my friend Murkthar Suleiman likes to say: “I want to die empty.” And I believe that too. I feel like my purpose is tied to words—speaking them, writing them. It’s my duty to write as much as I can, to tell the stories I carry, so I can die empty, with nothing left unsaid.

Your work, whether fiction or non-fiction, holds space for grief, longing, tenderness, even humour. When you’re writing, are you hoping to say something specific to the world, or is it more about listening to what the story wants to say to you?

It’s a little bit of both. Just by existing in this world, patterns, places, and circumstances shape you—they permeate your consciousness. So whether consciously or not, we’re always confessing the stories we’ve borne witness to. And I think that’s a really powerful thing about the arts in general.

Grief, longing, tenderness—these are human experiences, both collective and personal, so of course they’ll seep into my work. A lot of my writing is also about being a mirror, inviting society to see itself clearly, or to reimagine a different way of being, you know?

And I think this has always mattered. It’s why artists have had their works banned, why books have been burned, and why knowledgeable people (read as: women) were killed in the past. Art challenges dogma. Writing, especially, asks us to question what we’ve accepted as truth. People know the power it holds.

So, when I tell stories, I’m often asking readers to think. Please, think. See what the world has become because of you and me. Or imagine what it could become.

And then, I must add, there are times I just write for the sake of writing—without a grand agenda or deeper message. Especially when I’m writing poetry. Sometimes, it’s simply for the joy of it.

Your new collection, Not So Terrible People, is an intriguing work, a short story cycle of interconnected stories that are deep, beautiful, and otherworldly. It does this beautiful, haunting thing where the reader is made to sit with uncomfortable truths through characters who are funny, flawed, and painfully human. Much like Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, especially in his Dreams and Assorted Nightmares. What was the inspiration for you for this work? Where did this collection start for you, and at what point did it become the book it is now?

It’s very high praise to have Not So Terrible People (NSTP) compared to any of Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s works, so I’ll take that. Thank you very much. The collection actually started with the second story, Owanyi. Fun fact: it was longlisted for the SEVHAGE Prize for Fiction in 2023. But the story itself began as a writing exercise in 2014 or 2015, though I can’t quite recall the exact year. TJ Benson had created a group on Facebook called This Place, where writers like Hymar Idibie, Chinwendu Nwangwa, Ama Udofa, Victor Daniel, and I would share prompts. One day, TJ asked us to write a character whose voice really stood out. So I wrote Ebuka and his fiancée, Owanyi—just a lovely couple having a conversation in a kitchen.

In 2018, I watched an Indian film, Om Shanti Om, which revolved around reincarnation. I decided to explore that theme, and Owanyi shifted from a simple love story into one about a couple whose love is complicated by the girl’s reincarnation.

From Owanyi, I wrote about four more stories, which were just “by the way” pieces, until 2022. That year, I stumbled upon a Twitter thread about jinns and childhood memories of jinn manifestations in secondary schools around the North. I joined the conversation and shared my own experience cause back in school, girls would develop deep, masculine voices, incredible strength, and insane speed when jinns manifested, triggered by anything from anger to Quranic recitations. TJ saw my comment and encouraged me to document those school stories, so I began writing about jinns.

At first, these were just individual stories until I re-read Waiting for an Angel by Helon Habila—my favourite writer in the world. Reading it again flipped a switch in my head, and I realized that these stories could come together. The more I wrote, the more the collection took shape. I’m not sure exactly how it happened, but I’m so glad it did.

With Not So Terrible People, I wanted to tell fantastic stories, honour my childhood memories, and pay tribute to the Ebira blood that runs through my veins.

That’s a lovely story, and a good background story. Many thanks to TJ Benson, who has obviously had a significant impact on you and your writing. On the whole, drawing from what you have said now, part of what you have sought to achieve here is in line with postcolonial motives, honouring one’s roots and reclaiming one’s voice. Back to your Not So Terrible People, a brief question, many characters in the book walk the line between silence and expression. Were you consciously writing about the weight of the unsaid, or did that just emerge as the stories found their shape?

I hadn’t consciously thought about it until now, but I think the tension between silence and expression emerged organically as the stories found their shape.

We see themes like infertility, gendered trauma, and class running through the collection. Do you see these as political stories? Or do you prefer to think of them as just human ones?

For me, everything is political. And by political, just to be clear, I mean the way we, as humans, relate to ourselves, to the people around us, and to the institutions that shape our lives. I don’t believe we can separate the self from the politics of our existence. Even if I were to write about something like rest, rest would be political. In that sense, humanity itself, and the idea of being human, is inherently political.

Very briefly, the Abuja-Kaduna train attack finds its way into the book not as spectacle but as wound—personal, lived, intimate. You don’t write it as a headline; you write it as a heartbreak. What made you write that moment, and what does it mean for you to bear witness through fiction?

It happened. And as the days went by, it almost felt like everyone was forgetting or not acknowledging it. A train was derailed. A train was derailed! People died. People were held captive for months. It happened. And this is my way of bearing witness, of not turning away. This is me doing my part, because there’s nothing else I can do. It feels like a hopeless thing to say, but really, this is all I can do.

Thank you for keeping it brief. We shall explore this and more in another interview, specifically relating to the novel, NOT SO TERRIBLE PEOPLE. Let’s now talk about your award-winning piece, ‘We Bought an Album’ in June, which is a raw and beautiful work looking at loss, which is also set to be published by SEVHAGE, our publishing house, in June. Would you look at the coincidence? Anyways, what was the process of writing that piece and what demand, if any, did it place on you?

My birthday is in June. Can I get a box of chocolate to mark the publication and my birthday?

So, two things: I felt I needed to write about Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS), and I also wanted to honour the memory of my loss. I’m answering this question and getting really teary-eyed, but em, there’s a lot of shame and silence around women’s reproductive and sexual health. It’s often an area where I try to be as honest as possible, so that other women who’ve felt what I’ve felt can feel less alone—and for women who are looking for information, to get what they need to make informed choices.

Writing it was hard. I’d been trying to write that story since 2022, but I could only ever muster a few sentences here and there. It really came together in piecemeal, and with a lot of omission too—I left out or glossed over intricate details of hospital procedures, for example. Then, because I couldn’t really read it again, I gave it to Carl Terver to edit, accepted his suggestions, and submitted it before my nerves could fail me.

And now, having it published by SEVHAGE feels like such a full circle moment—almost like a quiet, personal triumph. It’s one thing to write something so raw and intimate, but to have it shared with a broader audience, especially through a platform that has supported my work, is incredibly humbling. It feels like the kind of recognition that makes all the difficulty and vulnerability worth it.

Professor Dul Johnson (multiple award-winning SEVHAGE author), Nana Sule (showing her plaque for the award of Winner, Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction), and S. Su’eddie Vershima Agema

Similarly, in Birthing the Mother (published by Isele and recognised in the Abebi Afro-Nonfiction Awards), you speak powerfully, tenderly, and painfully about motherhood, loss, and what it means to inhabit a body in flux. How do you choose what parts of your life to make public in this way? And like I asked previously, what was it like writing the piece? What does writing such pieces do to you, and what purpose does it serve?

After giving birth, I was on an emotional roller coaster, so I kept a journal for a while. Birthing the Mother was more like an excerpt from that, and it only took a bit of polishing.

When it comes to choosing what to share, I mostly like to write about my reproductive health. As I’ve mentioned before, this is my way of contributing to these conversations and making the information available for the women around me.

Not stirring too far away, one notes that your writing seems to lean against societal expectations – of what women should endure, of what home should mean, of who gets to grieve and how. Your blog, ‘Whereisize’ (on Medium) also tackles such issues. What has informed this continuous fight and is there any issue you think you might not want to really confront for any reason? Importantly, what’s one [or more] “norm” you’re still determined to rewrite through your work?

Living in the current politics of existence, I am here, surrounded by—if not directly, then indirectly—the linear expectations of what women’s lives should be: be born, grow up, birth kids, serve in the domestic sphere, be happy to exist within it. I write, sometimes, for women like me—women who love to wander, women for whom life is more, life is bigger than the box we’re expected to fit into.

It isn’t a fight; it’s an honoring of my existence. A documentation of the choices that have led me to be who I am, and a reflection on my views of the world. I think, for now, I am writing what needs to be written, and I am okay with the pace I’m going.

Leaving the depth of these experiences, let’s go for something light. You were also longlisted for the SEVHAGE/Leticia Nyitse Prize for Short Fiction with ‘Onwanyi’, which is part of your forthcoming book, Not So Terrible People. Can you reflect on your journey from one side of the prize to winning in another category and what these prizes generally mean to you, alongside the other awards you enter?

Haha. Interestingly, I entered both categories last year. Fiction is always my go-to genre, but it just didn’t work out for me in that category. Winning in the non-fiction category was such a pleasant surprise, really, and once again, I am so grateful for it.

Winning a prize —and I do not downplay the role of grace, luck, or whatever it is when the universe smiles upon you—feels validating. It’s such a good feeling, and I enjoy the moment, the attention, and the recognition.

On the other side of the winning coin, for me, is a belief that I have to keep working to hone my craft. I have to keep putting work out there, reaching a wider audience, and allowing my stories to travel. Because I believe the work of writing is never-ending. Prizes and awards are great when they come, but they only serve to remind me to keep writing.

You’ve lived in several cities, moved through different seasons of life. How do you think place shapes your storytelling, and do you think there’s a city or space that still has something to teach you?

Something in Naivasha, Kenya, calls to me. Let’s put it this way: Kenya calls to me because I also love Nairobi. I hope to have a reading there someday… Hey, that would be the perfect birthday gift, actually—a getaway to Naivasha to sip tea and write. Bliss!

I think place is an important ingredient in who we become and in the way we see the world. The places that have impacted me the most are Okene, Zaria, and Minna. Okene, for obvious reasons. Zaria, because a huge part of my formative years were there, so I’ve absorbed some cultures, ways of life, and even language. Minna, because of the people—TJ, David, Halima, Shammah, the Hilltop Art Center, ANA Niger, AMAB Books—and everything and everyone in between that made Minna the creative hub that it was, a hub that further refined my writing skills. I am grateful for these places and for the ways they’ve helped me see the world.

Finally, most writers have different reasons for writing but one paradox I read about somewhere is that of writing to remember and to forget. Drawing from this, what have you written that helped you forget, and what have you written that you hope never fades?

I hope that my roots are always reflected in my writing. I hope that never fades. I’m not sure that I want to forget anything now. I’m in this headspace, this phase of my life, where I understand the importance of remembering and the essence of memory. If anything at all, I want to document as much as is humanly possible. I want to remember.

About Nana Sule:

Nana Hauwa Sule is a Nigerian multi-genre writer, editor, communications strategist, and co-founder of The Third Space, an independent bookstore and creative hub in Kano. Her writing has received multiple honours, including co-winning the Eugenia Abu/SEVHAGE International Prize for Creative Non-Fiction (2024), being longlisted for the SEVHAGE/Leticia Nyitse Prize for Short Fiction (2023), and earning a notable mention in the Abebi Award in Afro-Nonfiction for her essay Birthing the Mother. A gender advocate and reproductive rights crusader, Nana’s work speaks boldly to the realities of womanhood, faith, and memory in a world constantly shifting between silence and sound. She blogs at https://whereisize.medium.com/ and tweets as @izesule on X.